I never really had a head for numbers… for dates and times in particular. Rather, language was my forte—you might say from word one — so in school, I found those salient facts I was to absorb from history classes fell away faster than the hours in a day.

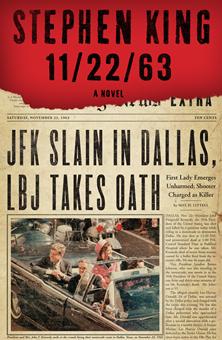

In any event, as a Brit, and a Scot, what history I was taught, whether I recall it or not, was the history of Britain, and of Scotland. Which is to say, before now — before immersing myself in the latest tome to come from the undisputed King of pop genre fiction — I couldn’t have told you very much at all about the significance of the 22nd November in the year of our lord 1963; the date the 35th President of the United States of America, the democrat John Fitzgerald Kennedy, was shot dead in Dallas, Texas by Lee Harvey Oswald.

Now JFK was not the first American President to be assassinated by some disillusioned so-and-so — in fact he was the fourth… I know these things now — and there would be unsuccessful attempts on the lives of several subsequent holders of the one office to rule them all thereafter, yet it is commonly thought that Kennedy’s death had such far-reaching ramifications as to alter not just the patchwork fabric of the United States, but that of human society entirely. And perhaps it did: borne as it is of the philosophy of chaos, which holds that everything — bar nothing — is uncertain, the butterfly effect may be far from a verifiable fact in and of itself, but science certainly concurs that from each and every action springs an equal and opposite reaction, and the assassination of arguably the most powerful person in the world is no exception to the rule.

11/22/63 begins with a bona fide believer in that theory.

No spoilers.

Al Templeton is owner and operator of a greasy spoon café in Lisbon, Maine, and sole purveyor of the house specialty: the Famous Fatburger. Cruelly, the Fatburger is more often called the “Catburger,” because the meat is so cheap, and how else Al can be making a buck on it is anyone’s guess. One day, however, having been given only weeks to live after a diagnosis of lung cancer, Al lets one of his best customers — namely Jake Epping, a largely luckless English Lit teacher, of late divorced — in on his secret: he’s been buying his beef by the kilo from a butcher who charges what was the going rate more than 50 years ago.

Crazy, right? Jake thinks so, too. He might be a bit miserable but he’s not mad. All the same, he means to humour this dying man as much as he can, so when Al offers to show him the basement, and then the pantry, and then the gate in time to 1958 inexplicably in the pantry, in the basement, Jake plays along. He steps through:

[…] and all at once there was a pop inside my head, exactly like the kind you hear when you’re in an airplane and the pressure changes suddenly. The dark field inside my eyes turned red, and there was warmth on my skin. It was sunlight. No question about that. And that faint sulphurous small had grown thicker, moving up the olfactory scale from barely there to actively unpleasant. There was no question about that, either.

I opened my eyes.

I was no longer in the pantry. I was no longer in Al’s Diner, either. Although there was no door from the pantry to the outside world, I was outside. I was in the courtyard. But it was no longer brick, and there were no outlet stores surrounding it. I was standing on crumbling, dirty cement. Several huge metal receptacles stood against the blank white wall where Your Maine Snuggery should have been. They were piled high with something and covered in sail-size sheets of rough brown burlap cloth.

I turned around to look at the big silver trailer which house Al’s Diner, but the diner was gone.

The idea of a tunnel through time in the basement of his local burger joint is a wild one, alright… but so far as Jake can see — and hear, and feel — it’s real. And after an initial exploratory trip around Lisbon a la the late fifties, taking in a root beer richer than any he’s ever tasted and an encounter with a doom-saying hobo Al calls the Yellow Card Man, there’s simply no denying it.

Returning to the diner, hat in hand — a fedora, don’t you know — Jake finds that only two minutes have passed in the present. He takes the day to decide that he’s not completely lost it, and returns too late to Al, who is, alas, not long for this world… or indeed the other. Before Al passes, however, he imparts to Jake his impossible mission, should he choose to accept it: to use the gate to assassinate the assassin before he can take JFK out of play. To live for five years in the past so that he might have the chance to change the world; or change it back to the way it would have been, or should have been, had Lee Harvey Oswald been stopped before he made it to that infamous spot on the sixth floor of the Book Depository. As Al puts it:

This matters, Jake. As far as I’m concerned, it matters more than anything else. If you ever wanted to change the world, this is your chance. Save Kennedy, save his brother. Save Martin Luther King. Stop the race riots. Stop Vietnam, maybe. […] Get rid of one wretched waif, buddy, and you could save millions of lives.

Thus the stalwart author arrives at the idea that animates so much of 11/22/63. If you were able go back in time and kill Hitler, or Stalin, or Bin Laden—stopping just short of Simon Cowell, or not—would you? Could you? Should you? Is murder any more righteous when the ends justify the means? What does tomorrow look like, without yesterday to inform its appearance? And not least: who are we, in lieu of who we were? These are among the many questions everyman Jake Epping wrestles with throughout the not-inconsiderable length of Stephen King’s most personable and satisfying novel in some time — and we with him, for in this vast first-person narrative we are always with him, from his first flirtations with the past through to his last.

It’s a hell of a ride, all told, and a perfectly comfortable one at that, for the larger part. Assuredly the author has had his moments since the turn of the millennium, foremost amongst them his 2008 effort, Duma Key, and another story named after a date: “1922,” the best of the four chilling novellas collected in last year’s Full Dark, No Stars. So too was there a lot to like about Under the Dome, but as is so often the way with King, and the fiction of the inexplicable that he has made his bread and butter, its resolution proved too pat to satisfy, undermining much of what had seemed till then meaningful, robbing that vast narrative of the impact it might otherwise have had. That said, I would argue that this past decade has been something of a renaissance period for the author oft-referred to as a modern-day Dickens; a grand tradition with great expectations of its own which I am happy to say 11/22/63 almost entirely satisfies.

Now 11/22/63 is a long novel — longer, no doubt, than it need be — but not such a sprawling or intimidating thing as Under the Dome. Rather than the fistful of protagonists who carried that narrative all the way to its bitter twist of a last act, King’s latest has only the one, and he’s not even a particularly complicated bloke: Jake is level-headed, liberal, and a little lost in life, so the idea of another life, in another era altogether, appeals to him a great deal. He’s not as yet entirely invested in Al’s objective, however, or even convinced that it’s possible for him to save the world in this way, because as he quickly comes to understand, “the past is obdurate. It doesn’t want to change.” And assuming for a moment that it can be changed, what, Jake wonders, might the consequences consist of? Will acting as a guardian angel to JFK leave us with a better world, or one the worse for wear?

So it is that, before he goes back in time for the long haul — the five years between 1958 and that fateful day in Dallas — Jake resolves to try a test case. And what better subject than the janitor Frank Dunning, whose harrowing personal essay — a true story explaining how he got the limp the kids at school mock him for — moved our man, who is not “what you’d call a crying man,” to fits of tears? Realising that the night Frank’s abusive father massacred his entire family — short its youngest son, who did not escape unscathed — correlates roughly to the day in 1958 that the gate in the pantry in the basement of Al’s Diner opens onto, Jake doesn’t hesitate: he travels back in time and takes to Derry, in an attempt to reverse this tragic turns of events.

11/22/63 is never better than it is during this episode, to which King devotes approximately the first third of his disarmingly straightforward time-traveling tome. The reader has every opportunity to get to know Jake a bit better, and though he is, as aforementioned, every inch the everyman — no more or less remarkable than the other ordinary folks whose extraordinary lives King has chronicled before — one finds oneself rooting for him from the first, so practiced (to near-perfection) is King’s craft in terms of characterisation. He may be a nobody, and nobody’s problem, but in short order he becomes our nobody, and we happily inherit his problems.

Setting is of course another of the estimable author’s strengths, and 11/22/63 showcases King on sterling form in that sense, for as we are coming to terms with our central character, Jake himself is getting to grips with life in the Land of Ago, which is to say the seedy underbelly of Derry by way of the Dunnings, then the gentle Americana of Jodie, an idyllic little town Jake settles in to wait out the years before he must take to the chaotic squalor of Dallas. I was for my part as hesitant to leave Jodie behind as Jake finds himself when the time finally comes, because these places, to a one, are characters in their own right; sketched so confidently that they seem thick with the sights and sounds of life, not to mention the stink of death. But of course death, because “Life turns on a dime,” doesn’t it? “Sometimes toward us, but more often it spins away, flirting and flashing as it goes; so long, honey, it was good while it lasted, wasn’t it?”

It’s actually pretty late in the game when we catch up to the high concept of 11/22/63 perhaps three quarters through the thing — I kid you not — so I dare say it wouldn’t do to talk too much about the climatic last act, far less the inevitable showdown between Jake and JFK and JFK’s cold-blooded killer, except to say (with regret) that 11/22/63 loses some of its steam at this stage, when by all rights there should be a gathering together of its many and various plumes. It doesn’t help that this moment, to which every other seems to build, has been so very long in the coming, nor does King’s rationale for so postponing the clash between past and present, fact and fantasy, quite cut the mustard:

Imagine coming into a room and seeing a complex, multi-story house of cards on the table. Your mission is to knock it over. If that was all, it would be easy, wouldn’t it? A hard stamp of the foot or a big puff of air the kind you muster when it’s time to blow out all the birthday candles would be enough to do the job. But that’s not all. The thing is, you have to knock that house of cards down at a specific moment in time. Until then, it must stand.

Because of the butterfly effect, basically. Because in all the years Jake idles away in the past, he’s not otherwise flapped his wings, has he? Well, of course he has. But King is at pains to distract Jake from this realisation until the time comes for it to suddenly dawn on him, for plot purposes, natch.

Saying that, though the day — you know the one — is itself a disappointment, apt to leave readers more deflated than fulfilled, in totality11/22/63 actually ends very well, feeling neither cheap nor a cheat in the mode of so many of King’s past works. For myself, I don’t much mind how the conclusion came about, but it is interesting nonetheless to note that the author took to heart his son Joe Hill’s suggestion of a new and improved ending. What with the track record of ropy reveals that have inhibited King’s fiction from the very beginning, I do wonder how things might have panned out otherwise .

But if I could pop back in time and see the first draft of 11/22/63? I don’t know that I would want to, truth be told, because as it stands the new Stephen King seems right enough; true to its characters and its themes, and consistent — not to mention consistently thrilling — in its mood and tone, and its bittersweet, fatalistic sense of the inevitable. Though it has a little of the Final Destination to it, and in the early-going, sure, a touch of Groundhog Day, too, 11/22/63 is its own ineffably King-ish thing for the larger part: a charming, relaxed and nostalgic trip through time which takes in conspiracy, consequence and catastrophe with the same effortlessly endearing cheer that has made the work of this natural — nay, masterful — storyteller such a pure and simple pleasure to read through the years.

11/22/63 may not change the world, in the end, but it might very well change the way you think of it.

And isn’t that pretty much the point?

Niall Alexander admits ignorance with alarming regularity inreviews of all the shapes and sizes of speculative fiction he’s partial to in the pages of Starburst Magazine and Strange Horizons, or failing that on his blog, The Speculative Scotsman.